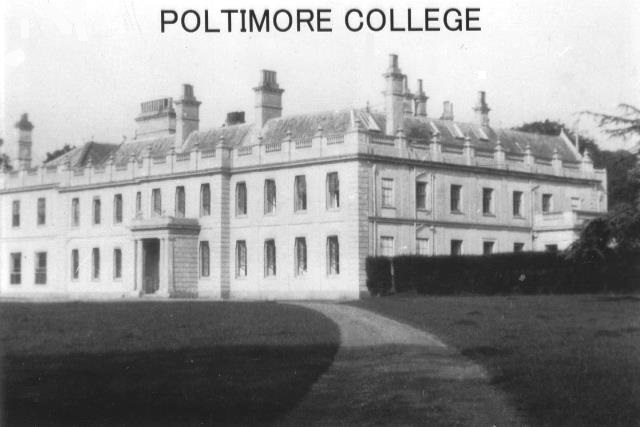

According to the North Curry Parish Magazine for September 1923, the departure of Newport School from Wrantage was a cause of regret. The children were taken by charabanc to view their new premises in Devon and treated to a strawberries-and-cream tea on trestle tables set outside the main front of the house. They were delighted. The school changed its name to Poltimore College, and the life of the house took on a completely different aspect.

The deer still grazed under the oaks in the park, however, looked after by George Lindsay and Albert Thorne, who lived in the Old Lodge and became groom to Miss Celia Wontner, The Principal of the school (always known as The Head). The Head brought with her from Wantage her general factotum, Harold Lane, who settled at The Kennels after George Lindsay died. Many of the original Poltimore Staff stayed on to work for the new management; William Aldridge, for instance worked as woodman, gardener and blacksmith. In spite of the fact that he had lost his right arm as a result of a circular saw accident, with a steel hook strapped on to the amputated end he was able to drive a tractor, or the pony cart and, most important of all, he was the one man who could fire the temperamental gas engine for generating electricity.

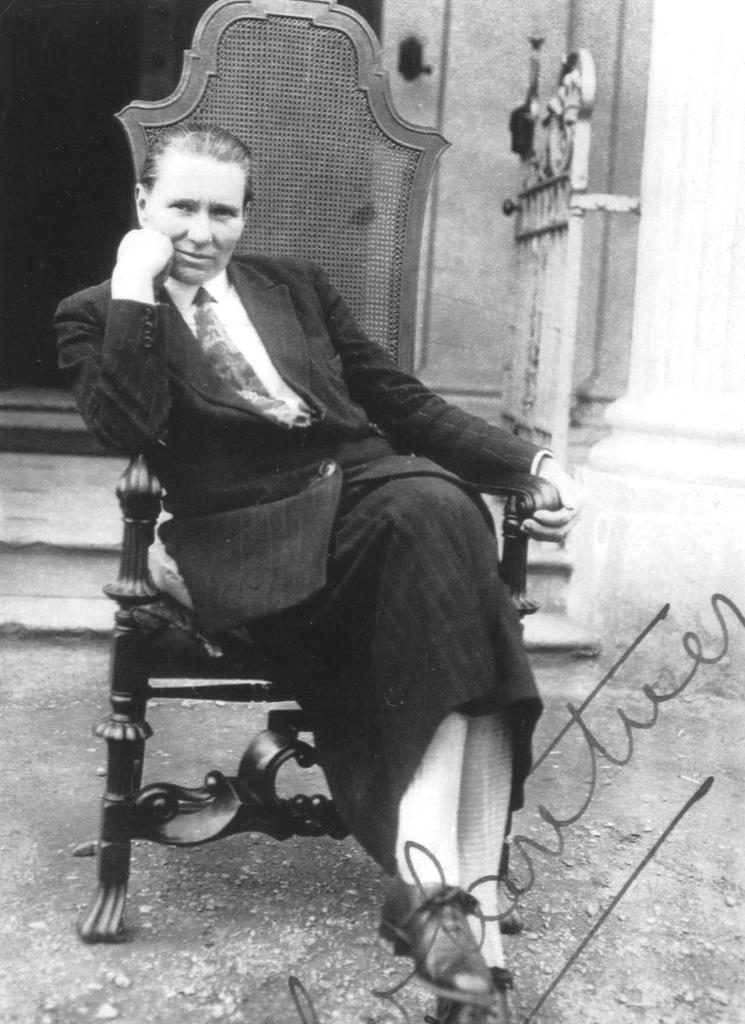

According to accounts given by former pupils of Poltimore College the girls were allowed no contact with the village, neither at the shop and post office, or the church, as the College built a chapel, timber-framed and clad and roofed in asbestos, in a space behind the west wing of the house. In this The Head, who came of the theatrical Wontner family, used to preach dramatic sermons, which were listened to with some reverence.

Many former pupils have said that living in such a beautiful place as Poltimore contributed to their schooldays being happy ones. One who was at the College from 1925 to 1928 remembers the feeling of welcome the house gave, and how she was interested in her reactions even at a young age. For another, however, the grand staircase held particular memories, for the head used to hold court there every morning and all those pupils who had misbehaved were lined up on the left side to be suitable admonished – so this pupil, who was invariably in hot water, spent a lot of time quaking in her shoes on the stairs.

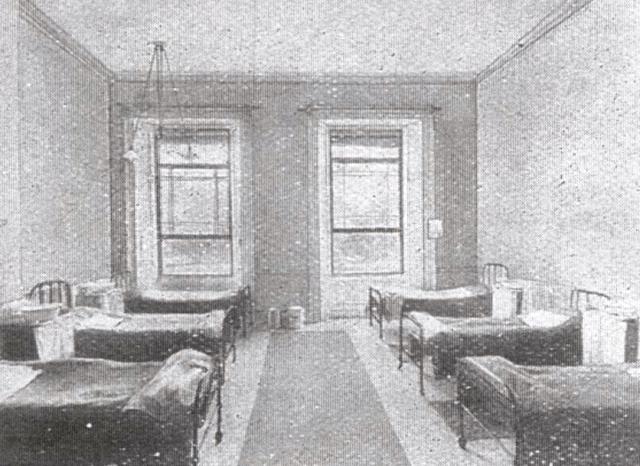

There was a great contrast between being taught in lofty classrooms, studying in the school library, installed in the 18th-century white and gold Saloon, and passing up and down the grand staircase where some of the Bampfylde portraits still hung, and the spartan nature of the dormitories with orange boxes for lockers and only cold water for washing, which of course had ice on it on winter mornings. The prefects had quite cosy studies up in the attics and the wide path in the central avenue of cedars was termed ‘the prefects walk’, from which lesser mortals were excluded.

The food was never enough, only one decent meal a day, but a twice-yearly treat was roast venison after the cull of the deer. One pupil, at the age of nine, so hated her first week at Poltimore, and in particular the school breakfasts of bread and porridge, that she climbed out of a downstairs window and ran across the park to New Lodge, where the Aldridges took charge of her and escorted her back to the school. Fortunately, the cuisine improved and the rest of her four years in the splendid surroundings of the house and park are now recollected in tranquillity.

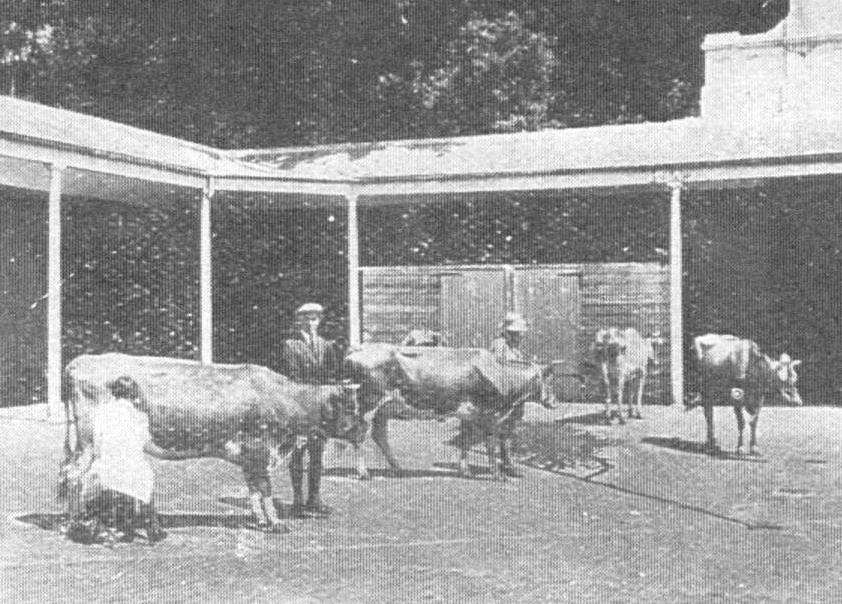

There were many outdoor activities, keeping hens and golden pheasants in the former aviaries and even learning to milk cows in the stable yard.

The Aldridges looked after the main hockey pitch in front of the house, reckoned to be almost the best in Devon, and was often used for county matches. Tennis courts were laid out on the east lawns and a swimming pool dug in the stream by the Chinese Garden.